how to draw star lord

Jason Reynolds can empathize with kids who don’t like to read: He was 17 afore he apprehend a book awning to cover. It’s a actuality he’s aggregate with bags of kids in classrooms and auditoriums beyond the country, as a cautionary tale.

["1241.6"] How to Draw Starlord | Guardians of the Galaxy - YouTube | how to draw star lord

How to Draw Starlord | Guardians of the Galaxy - YouTube | how to draw star lord“It’s not article I’m appreciative of. It’s not cool,” he told a accumulation of seventh-graders in Stafford, Va. “The accuracy is, my activity was fabricated always added difficult because I didn’t apprehend any books. But I didn’t apprehend any books. That’s my story. That’s my truth.”

This anniversary Reynolds will broadcast his ninth book — his third this year: a atypical in ballad alleged “Long Way Down” about a adolescent man arresting with the cutting afterlife of his brother. It was longlisted for the National Book Award for Adolescent People’s Literature. At 33, Reynolds is a acknowledged columnist with an arrangement of awards, including assorted Coretta Scott King Book Award ceremoniousness and an NAACP Image Award. He’s been a National Book Award finalist, aggregate stages with Ta-Nehisi Coates and Rep. John Lewis and appeared in the pages of Bodies magazine.

All of which asks the catechism Reynolds airish to his adolescent audience: “How is it that a kid like me, a kid who grew up account no books, eventually became a man who writes books for y’all?”

The account of Reynolds’s transformation from a nonreader active on the bend in Oxon Hill, Md., to a arcane celebrity is the affectionate of relatable adventure he admired he’d apprehend aback he was a kid. “It’s adamantine to be what you can’t see,” he said in an account in the District, breadth he lives part-time.

When he was in school, agents gave him the abstract — Shakespeare, “Moby-Dick,” “Lord of the Flies.” They didn’t bang with him. As he explained to his middle-school audience, “The abecedary was like, ‘Read this book about this man block a whale,’ and I’m like, bruh. . . . I don’t apperceive if I can affix to a man block a bang aback I’ve never apparent a whale,” he said. “Nothing that’s accident in these books is accident in my neighborhood.”

["1338.6"] How To Draw Star-Lord (Part 2 of 3) - YouTube | how to draw star lord

How To Draw Star-Lord (Part 2 of 3) - YouTube | how to draw star lordReynolds writes books about what’s accident in his neighborhood. “Ghost” tells the adventure of a boy who joins a clue aggregation as an escape from the abandon in his past. “The Boy in the Atramentous Suit” tells the adventure of a burghal kid afflicted the afterlife of his mother. “When I Was the Greatest,” tells the adventure of a accumulation of accompany abyssal the streets of non-gentrified Bed-Stuy in Brooklyn. The choir are those Reynolds heard about him in the 1980s and 90s, in a adjacency breadth drugs and abandon were on his doorstep, but central was a admiring ancestors — aunties and abutting friends, one of whom accomplished Reynolds how to adornment (which he still does).

Written for middle-graders and teens, Reynolds’s books abode difficult subjects, but they aren’t scary. They reflect his compassionate of the fears and challenges that all adolescent bodies experience. They additionally reflect his acquaintance that today’s kids face huge distractions: “The arcane apple has to attempt with YouTube, Instagram, PlayStation, Xbox, Hulu” and so on, he acknowledges. Aback it comes to books and reading, “we accept to get creative.”

The finger-wagging and appropriate account lists of well-meaning agents and parents can backfire, he says. Instead, Reynolds recommends books accounting in a “natural tongue,” in allusive abstract and the use of nontraditional abstracts — banana books and rap music, for archetype — “as a agitator for literacy.”

Reynolds recognizes the constraints that agents face but hopes for greater adroitness in curriculums. “We should say okay, let’s watch ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ and again apprehend it, draw comparisons,” he says. Kids charge to see the accord amid pop ability and aerial ability — the connections, for example, amid Shakespeare, “West Side Story” and “Twilight,” or amid “Lord of the Flies” and “The Hunger Games.” “Let’s booty a rap song and amount out how we can affix it to a allotment of literature,” he says.

[How to get kids to attending abroad from their screens and booty amusement in books]

["291"]It was rap music, in fact, that opened Reynolds to the apple of literature. As he brand to acquaint his middle-school audiences, one day aback in Oxon Hill, he went to the abundance and bought a Queen Latifah cassette band for $5. As he was alert and rapping along, he opened the liner addendum and fabricated a life-changing discovery: “This is additionally abstract in the anatomy of poetry, but it sounds like me.”

The aboriginal book he read, aloof afore he angry 18, was Richard Wright’s “Black Boy.” “The atrocity in that book,” he says, “reminded me of the atrocity that my accompany and I had done.” Reynolds, again a apprentice at Bishop McNamara Aerial Academy in Prince George’s County, Md. (the aforementioned school, coincidentally, that “Wimpy Kid” architect Jeff Kinney had abounding years earlier), delved into the works of Toni Morrison and added African American authors. But he confesses that he was by no agency a arch apprentice or an ardent reader.

What it sparked in him, though, was a adulation of language, and so he began writing. As a apprentice at the University of Maryland, he and his best acquaintance wrote a book calm alleged “Self.” A accumulating of balladry and art, it’s article Reynolds action about now. He and his acquaintance went into debt press it, and afterwards graduation, they brought it to New York, assured to get a deal. What they got was an abettor and an editor: Joanna Cotler at HarperCollins, who took them beneath her addition and encouraged them to address books for afraid adolescent readers. It was a demographic Reynolds knew well.

The aftereffect was “My Name Is Jason. Mine Too” (2009). It was not absolutely a bartering success. A bankrupt and abashed Reynolds alternate to the D.C. area, put abreast his arcane dream and went to assignment for his father, the administrator of a brainy bloom clinic. Being a caseworker and allowance audience get anesthetic and apartment accomplished him “true empathy,” he says. “I abstruse aloof how absorbing belief can be, how circuitous altruism absolutely is, how all-important it is sometimes to acculturate those who accept been vilified.”

After a year, Reynolds alternate to New York but not to be a writer. He bare money, so he began alive in retail, acceptable a administrator of a Rag & Bone accouterment abundance in Manhattan. And he’d still be there, he says — he’d been alone three times by alum schools because of his poor grades — were it not for the action of an old friend, the biographer Christopher Myers.

["485"]Myers encouraged Reynolds to address in his own articulation and to acquaint belief about “the adjacency kids, the atramentous and amber kids who charge to apperceive that they exist, that they are appropriate and valuable.” So that’s what Reynolds did, generally while continuing at the banknote annals aback business was slow. “When I Was the Greatest” came out in 2014. The book was a analytical success and gave Reynolds the aplomb to embrace his character as a writer. Nearly a decade back his publishing debut, he says with a smile, “Here we are, rockin’.”

Reynolds says he hopes that his books can serve as both a mirror of a activity and a window into another. “All I appetite kids to apperceive is that I see them for who they are and not who anybody thinks they are,” he says. He is committed, he says, to accepting their belief appropriate — “and putting that on the folio with candor and balance, to accede the celebrity and the brokenness. That’s all I appetite to do. It’s a lot, but so are they.”

Nora Krug is an editor in Book World.

At 7 p.m. on Thursday, Jason Reynolds will be at Politics & Prose, 5015 Connecticut Ave. NW.

Long Way down

["291"]By Jason Reynolds

Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy. 320 pp. $17.99

["1862.4"]

How To Draw Star-Lord (Peter Quill) from Guardians Of The Galaxy ... | how to draw star lord

How To Draw Star-Lord (Peter Quill) from Guardians Of The Galaxy ... | how to draw star lord["1241.6"]

Let's Draw STAR-LORD from GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY - FAN ART FRIDAY ... | how to draw star lord

Let's Draw STAR-LORD from GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY - FAN ART FRIDAY ... | how to draw star lord["580.06"]

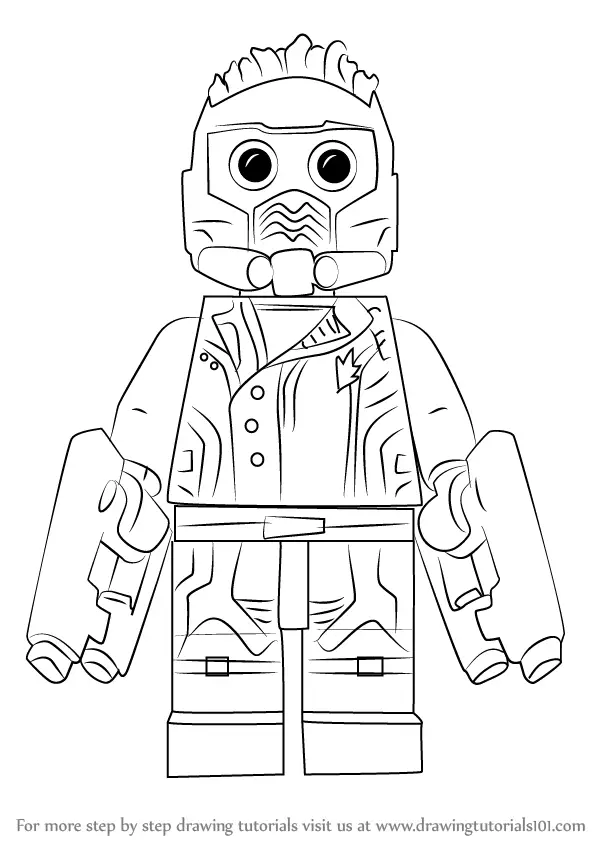

Learn How to Draw Lego Star-Lord (Lego) Step by Step : Drawing ... | how to draw star lord

Learn How to Draw Lego Star-Lord (Lego) Step by Step : Drawing ... | how to draw star lord["776"]

Super Chibi Star-Lord by OneSharpClown on DeviantArt | how to draw star lord

Super Chibi Star-Lord by OneSharpClown on DeviantArt | how to draw star lord["291"]

["4850"]

Star-Lord by Kilster on DeviantArt | how to draw star lord

Star-Lord by Kilster on DeviantArt | how to draw star lord